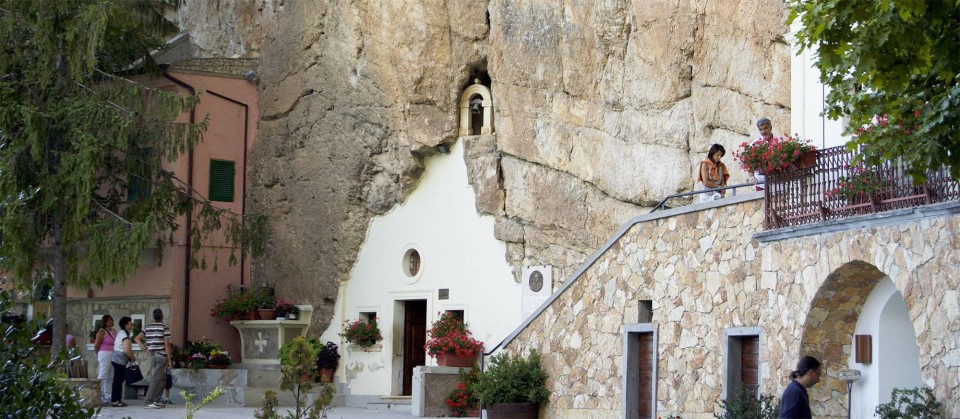

Site

Pie vienas no lielākajām Centrālitālijas augstienes apgabaliem un Simbruini kalnu reģionālā parka centrā, atrodas mazā Svētās Trīsvienības svētnīca (Ļoti svēta Trīsvienība). Vietne atrodas zem a 300 m klints seja. Pateicoties šim ikoniskajam izskatam, tas bija dievkalpojuma centrs jau pirmskristietības laikos. Vairāk nekā tūkstošgadi, galvenais godināšanas objekts ir bijis netipisks Svētās Trīsvienības tēls, krāsots bizantiešu stilā uz kailas klints vienā no daudzajām apkārtnes grotām. Ikgadējā Trīsvienības dienā (40 dienas pēc Lieldienām), tūkstošiem cilvēku no ciematiem rādiusā 50 km pulcējas šeit. Viņi uzturas trīs naktis un dienas, kurās viņi nemitīgi dzied un lūdz. Daudzi ierodas pastaigā vai jāj vairākas dienas, pa maršrutiem, ko jau sen izmantojuši ganāmpulka gani. Svētceļojums un svinības Svētā Trīsvienība joprojām ir viena no visīstākajām tautas dievbijības izpausmēm visā Itālijā un Rietumeiropā.

Draudi

Pēdējos piecpadsmit gados, apbūvētā teritorija ap svētnīcu ir palielināta, lai uzlabotu komfortu un drošību desmitiem tūkstošu ikgadējo svētceļnieku. Blakus ikgadējam tradicionālo svētceļnieku pulsam, Apmeklētājus visu gadu arvien vairāk piesaista svētnīcas reputācija par krāšņām žēlastībām, un tās pieejamības un infrastruktūras uzlabošana. Ja neatlaidīgi, šī tendence varētu apdraudēt dažas vietnes dabas un estētiskās vērtības. Sugām bagāto zālāju un vērtīgo silvo-pastorālo mozaīku uzturēšanu ap šo vietu apdraud arī lopkopības un saglabāšanas pasākumu samazināšanās.. Tie daudzus gadus bija priviliģēti mežu atjaunošanai, izmantojot tradicionālos apsaimniekošanas veidus, piemēram, medību un pamežu apsaimniekošanas ierobežojumi. Beidzot, pastāvīga reliģisko rituālu normalizēšana var radīt zaudējumus unikālajam nemateriālajam kultūras mantojumam, kas saistīts ar šo vietu.

Vīzija Tuvākajā nākotnē, tas būtu vēlams: (1) palielināt gan galveno ieinteresēto personu, gan plašākas sabiedrības izpratni par vietnes pilno vērtību spektru; (2) vairāk atbalsta pašreizējos parka pārvaldes centienus izmantot biokultūras pieeju saglabāšanai; un (3) mudiniet galvenās ieinteresētās personas vienoties par kopīgu un ilgtspējīgu vietnes nākotnes redzējumu.

Aizsardzības instrumenti Lai gan formāli aizsargāts, dabas un nemateriālā mantojuma saglabāšana šajā svētajā dabas vietā gūtu labumu no apzinātākas pieejas, piemēram, iedvesmojoties no IUCN-UNESCO svēto dabas vietu vadlīnijas aizsargājamo teritoriju pārvaldītājiem. Kā pirmais solis, kopš tā laika ir veikti īpaši pētījumi 2010, ar mērķi izprast vietas biokulturālo unikalitāti ar ekoloģisko palīdzību (floristikas aptaujas, telpiskā analīze) un sociālo zinātņu metodes (dalībnieku novērošana, etnogrāfiskās intervijas, fokusa grupas).

Rezultāti Līdz šim pabeigtais izpētes darbs ir pierādījis apgabala ekoloģisko vērtību un tradicionālo aktivitāšu, piemēram, svētceļojumu un dzīvnieku ganīšanas, savstarpējo atkarību.. Ir apkopotas dažas vietējo iedzīvotāju vēlmes un perspektīvas par turpmāko attīstību. Šie centieni tādējādi ir izcēluši ar svētnīcu saistītā nemateriālā mantojuma unikalitāti, atbalstot prasību par biokultūras pieeju saglabāšanai. Šie ieskati tiek paplašināti, lai sniegtu informāciju diskusijās par vietnes pārvaldību un pārvaldību, un tuvākajā nākotnē sagatavot koalīcijas veidošanas procesus.

Ekoloģija un bioloģiskā daudzveidība

Vietu raksturo karsta klinšu veidojumi un biezs dižskābaržu mežs, kas ir arī apkaimes nozīmīgākās ūdensteces avots, Simbrivio upe. Apkārtējos plato, sugām bagāti zālāji, ko veido dzīvnieku ganīšana, laiku pa laikam pārtrauc mežu. Senākie koki, bieži pollarētas vai līdzīgi pārvaldītas, ir sastopami šajos zālāju plankumos. Reta populācija Eriophorum Latifolium aug akmeņainos biotopos virs svētnīcas. Vilki no jauna apdzīvo teritoriju.

Aizbildņi Svētnīca atrodas Anagni bīskapijas jurisdikcijā, kas ieceļ atbilstošu priesteri (rektors) lai to uzraudzītu. The rektors atvēršanas laikā uzturas uz vietas (No maija līdz oktobrim) un pārrauga svētnīcas uzturēšanu un reliģisko izmantošanu. Ievērojama loma un neatkarība galveno svētku organizēšanā ir vietējo iedzīvotāju brālībām, un tieša līdzdalība vietnes pārvaldībā. Ar pēdējo ciešāk saistītas brālības ir Vallepietras, tuvākais ciems, un Subiaco, tuvējā pilsēta, kur pieķeršanās Svētā Trīsvienība pārvēršas sarežģītā rituālā visu gadu. Lai gan formālu ierobežojumu nav, piederība brālībām parasti tiek pārmantota un, Subiaco gadījumā, līdz pavisam nesenam laikam bija tikai vīrieši. Plakanumi ap svētnīcu ir vietēji īpašumā esošie kolektīvi silvo-pastorāli īpašumi. Ņemot vērā tradicionālo ekonomisko aktivitāšu samazināšanos un spiediena samazināšanos uz resursiem, tās jau vairākus gadu desmitus ir pieejamas arī nepiederošām personām apmaiņā pret gada maksu.

Strādājot kopā Pašlaik, vietnes pārvaldība joprojām ir samērā sadrumstalota. Neskatoties uz sadarbības mēģinājumiem, joprojām šķiet, ka visām galvenajām ieinteresētajām personām nav vienprātīga redzējuma, tas ir, vietējie iedzīvotāji, administratori, Baznīca, un parka vadība. Lauku attīstības veicināšana parka izveides brīdī tika definēta kā galvenais mērķis. Tomēr, vietējie iedzīvotāji apgalvo, ka tradicionālajam vietējam mantojumam ir pievērsta maz uzmanības, un administratīvo skandālu dēļ ir pieaugusi skepse. Kopumā, šķiet, ka galvenās ieinteresētās personas galvenokārt koncentrējas uz kādu konkrētu, tām svarīgu vērtību, bet šķiet, ka nav integrēta redzējuma par savstarpēji saistīto garīgo, vietas kultūras un ekoloģiskās vērtības.

Politika un tiesības Parks tika izveidots ar Lacio reģionālo likumu 1983 un daļēji pārklājas ar Eiropas Natura 2000 tīkls. Tā platība ir aptuveni 300 km2, neskaitot augstienes, kas pieder pie kaimiņu reģioniem (Abruco). Minimāla iejaukšanās pārvaldība “dabai”, ko īsteno un veicina Natura 2000, nav adekvāta, lai optimizētu kultūrainavu saglabāšanu teritorijā. Šī pārvaldība bez izšķirības piemēro "dabiskuma" ideju visiem biotopiem, un neatzīst tradicionālās ražošanas prakses nozīmi (piemēram, pastorālisms, ilgtspējīga lauksaimniecība, un apakšstāvu vadība) bioloģisko vērtību radīšanā. Vietējās grupas, piemēram, dzīvnieku gani, ir maz balss lēmumu pieņemšanas mehānismos, neskatoties uz to, ka tās pārstāv galvenās tradicionālās darbības. Citi spēlētāji, piemēram, Baznīca, ir īpašas intereses, ko virza reģionālās vai valsts prioritātes. tāpēc, pārvaldības režīmi, ko iedvesmojusi IUCN V kategorijas aizsargājamās teritorijas, šķiet piemērotāki.

Uz Tu pavērsi acis Cilvēks slāpju nomocīts Un uzreiz akmeņi Pilnībā lēja ūdeni - Tradicionāla dziesma Svētās Trīsvienības slavināšanai.

- Frascaroli, F., Bhagvats, S., Guarino, R., Chiarucci, A., Šmids, B. (presē) Svētnīcas Centrālajā Itālijā saglabā augu daudzveidību un lielus kokus. AMBIO.

- Frascaroli, F., Verschuuren, B. (2016) Biokultūras daudzveidības un svētvietu sasaiste: pierādījumus un ieteikumus Eiropas sistēmā. In: Agnoleti, M., Emanuels, F. (eds.) Biokultūru daudzveidība Eiropā, Cham: Springer Verlag, p. 389-417.

- Frascaroli, F., Bhagvats, S., Dīmers, M. (2014) Dziedinošie dzīvnieki, dvēseļu barošana: etnobotāniskās vērtības svētvietās Centrālajā Itālijā. Ekonomiskā botānika 68: 438-451.

- Frascaroli, F. (2013) Katolicisms un saglabāšana: svēto dabas vietu potenciāls bioloģiskās daudzveidības pārvaldībai Centrālajā Itālijā. Cilvēka ekoloģija 41: 587– 601.

- Fedeli Bernardini, F. (2000) Lai neviens neiet uz zemi bez mēness: Svētceļojuma etnogrāfija uz Vallepietras Svētās Trīsvienības svētnīcu. Tivoli: Romas province.