With this article we would like to invite you to think creatively and critically about the role of science and by extension those of conservation and policy-making in relation to sacred natural sites. In particular, we invite you to consider the significance that sacred natural sites hold in the eyes of their custodians and communities (for an example of such a perspective, see A Statement of Custodians of Sacred Natural Sites and Territories, 2008).

In its work, the Sacred Natural Sites Initiative (SNSI) supports custodians and their communities to protect, conserve and revitalize sacred natural sites. Taking an endogenous approach on the ground, SNSI supports custodians in identifying and building on their own visions, strengths and resources and then helps them match this with appropriate external resources and relations. SNSI also assists in making custodian voices heard in the international conservation and policy-making arena. It is of invaluable importance that supporters of sacred natural sites and their custodians work together, share experience and have access to the latest knowledge and materials.

A meeting to discuss research and protocols for safeguarding the sacred groves of Tanchara Community in north west Ghana. The Centre for Indigenous Knowledge and Organisational Development in Ghana has been supporting long term community research which has resulted into a community protocol. The process that required the community to establish agreements and work with several external NGO’s – such as the Sacred Natural Sites Initiative – and resulted in a moratorium on gold mining and a conservation plan for their sacred groves. Source: Daniel Banuoku Faalubelange.

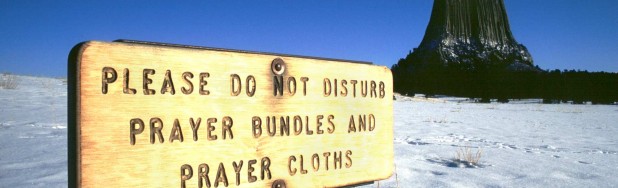

Working directly with custodians of sacred natural sites – such as indigenous peoples and faith groups – immediately exposes one to different ways of knowing and seeing the world. These diverse worldviews have much to offer to governance, science and management in general, but are especially critical to the survival and conservation of most sacred natural sites. Although international institutions are increasingly acknowledging that custodians and their communities can be effective stewards of biological and cultural diversity, there is still a long way to go for the recognition of sacred natural sites themselves. The same is true for respecting the intrinsic, human, cultural and religious rights of their custodians.

How then can we improve recognition and respect for the importance of sacred natural sites, including the meaningful relationships that their custodians and communities have developed with those sites, often over many generations?

Working together with SSIREN and SANASI (the world database on sacred natural sites) has given us the opportunity to exchange ideas and improve our own responses to this question, and this is increasingly reflected in the way we organize our work and attitudes. We recognise that much of this comes down to maintaining an ongoing process of consultation with custodians and experts, as well as applying the right ethics, guidelines and Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) protocols, where that is required. Taking ethics into account in the field of science can be especially challenging because of different opinions on what constitutes good science and how it should be practiced.

In our collaboration with SANASI we stumbled across this quote taken from an article on the Mijikenda Kayas (sacred forests on the coast of Kenya) by Kaingu Kalume Tinga, a scientist manager of a community-based organization (Kalume Tinga, 2004):

Constructive research has been inhibited because the traditional custodians are extremely conservative and also because of the researchers’ lack of openness about the aims and objectives, rights, obligations and benefits of the research projects to the community. Informants thus withhold invaluable information as security against the scholars; they also tend to be apprehensive of researchers from outside their community. Lastly, following the research, host communities do not receive feedback from the results – the findings are either too scientific for consumption by the host communities or they have no access to the information.

This quote gives a clear message – Custodians may welcome science, especially when they see they have a part in it, may control the process and see that the results can help further their cause. However, there are also those who have negative experiences, have become sceptical or believe that other, external ways of knowing such as science have less of a role to play in relation to their sacred natural sites. An example of the latter can be found in the Statement of Common African Customary Laws for the Protection of Sacred Sites (2012).

The preliminary platform on Protocols and Guidelines which you can find under the Approaches and Methods section.

Both-Ways Management from Australia (Yunupingu and Muller 2009), and Two-Eyed Seeing in Canada (Bartlett et al. 2012) represent powerful experiences and expressions of combining western and indigenous science, beliefs and practices into a mutually respectful and powerful approach to ways of knowing. These examples hint towards a model where researchers are asked for an open attitude in developing the research; questions, design, data collection, analysis and sharing of results are carried out in a participatory and interdisciplinary manner.

While it is true that most universities and research institutes nowadays have an ethical code of conduct for research, these have not been specifically developed to include all sensitivities related to sacred natural sites. The Code of Ethics of the International Society of Ethnobiolgy (ISE, 2006) is probably the most comprehensive guidance invoking an overall principle of ‘mindfulness’ in research and laying out processes for Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), and would be worthy of greater promotion.

A community of practice for learning from eachother’s experiences and improving the tools, methods and approaches available could be extremely valuable to the conservation of sacred natural sites. We would therefore like to invite researchers, practitioners and custodians to share their experiences and opinions. To those of you interested, we would also recommend taking a closer look at the guidance, protocols and codes of ethics that are available in your field to see if they are cognizant of the views held by custodians. We aim to collect and collate your views and consolidate them into a document that we can then return to you for discussion and revision. With sufficient support, a long-term goal could be to develop a ‘code of conduct” for researchers and conservation practitioners that work on sacred natural sites. Even sooner, and depending on your enthusiasm and responses, we plan to develop a Top 10 Guidelines for Researchers and Conservation Practitioners, which we propose to present in a forthcoming issue of SSIREN.

We are grateful for your input and also appreciate any links and materials that you think we should share with others through the platform on Methods and approaches that we are building as a resource for everyone. Please contact us at info@sacrednaturalsites.org and, for those who would like some more background feel, do not hesitate to download the introduction chapter to Safeguarding Sacred Natural Sites.

References

Bartlett, C., Marshall, M., Marshall, A., 2012. Two-Eyed Seeing and other lessons learned within a co- learning journey of bringing together indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 2(4): 331-340.

International Society of Ethnobiology (ISE), 2006. International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics (with 2008 additions). http://ethnobiology.net/code-of-ethics/

Kalume Tinga, K., 2004. The presentation and interpretation of ritual sites: the Mijikenda Kaya. Museum International 56(3): 8-14.

Yunupingu, D., Muller, S., 2009. Dhimurru’s Sea Country Planning journey: opportunities and challenges to meeting Yolngu aspirations for sea country management in Northern Territory, Australia. Australasian Journal for Environmental Management 16: 158–167.