"Prior to 1991 the complex was primarily visited only by the Pa’oh and was largely obscured from the larger world, to the extent that even in Taunggyi the general population was unaware of its location or existence" - Liljeblad 2016.

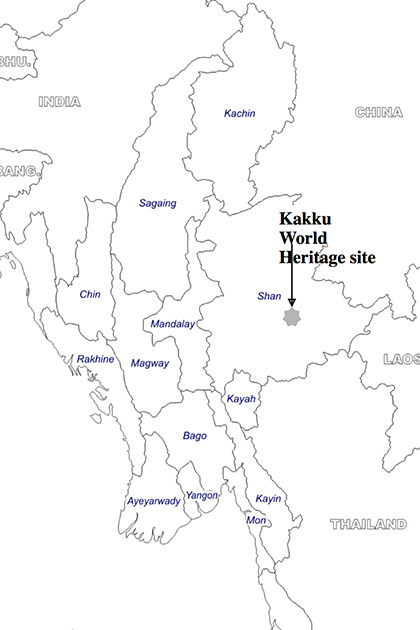

Site Description

Kakku is a remarkable sacred natural site, housing at least 2478 pagodas and a large number of sacred Bodhi trees. It is located in the Shan state in Myanmar, southeast of the city Taunggyi. Some say it is built as a shrine for the passage of the dead. Others claim that King Alaung Sithu built the site as a resting point for river travelers. Others yet see the location as having substantial spiritual properties, based on its astrology. All stories share their respect for the present sacred endemic Bohdi tree. The site currently faces the threat of being highly altered by tourism, something the government tries to stimulate. To mitigate this process, the local gawbaka committee creates ways to promote the local culture and raise awareness on their spirituality.

Threats

Threats to the biodiversity in the region include hunting and poaching, agricultural use of natural forests, shifts in cultivation methods, destructive fishing methods, introduction of invasive species and weak law enforcement against illegal activities such as wildlife trade.

Meanwhile, economic incentives such as development pressure and increased tourism drive local communities to concessions. Examples in Kakku are recent establishment of strong roads, the conversion of forest into farmland, increased village sizes and establishment of a parking lot and a restaurant, all of which came at the cost of local wildlife. According to archaeologists, the pagodas are threatened by bad reconstruction materials, which do more damage on the long run. As for the cultural context, some argue that regarding the Kakku site as a monument to preserve undermines local people’s capacity to undergo cultural evolution, and detaches local culture and identity from the site.

Vision

There is an intrinsic conflict of visions between the World Heritage system and the lived reality of the Pa’oh people, concerning the way to document the Kakku site. The national level registration and documentation of the local values is prone to adopt globalising notions on indigenous spirituality. It anchors the values of indigenous communities and overlooks evolving, dynamic conceptions of values towards their sacred sites. It raises questions on who has the authority to determine the meaning of a sacred natural site, and if categorization is always the best approach.

Action

The Pa’oh gawbaka exercises management of Kakku, and maintains an ongoing management approach towards Kakku involving regular consideration of site conditions and conservation policies. The jurisdiction of the gawbaka, however, is subject to an informal arrangement between the national and state governments with the Pa’oh, and the nature of this arrangement may change as Myanmar continues its political transition, which involves potential shifts towards federalism and attendant shifts towards indigenous ethnic communities.

Policy and Law

As it is a part of the country of Myanmar, the area has a range of wildlife and park protection laws in place (though not always properly enforced). More relevant in the discussion are the IUCN protected areas and ICOMOS cultural heritage guidelines, because they are more focussed on the interaction with the indigenous people at the site, and work towards greater inclusion. Indeed, recent reforms have introduced local indigenous values and authenticity in policy making, but the tendency to document and fix certain practices can be limiting for existing and evolving traditions.

Ecology & Biodiversity

Myanmar is part of the Indo-burma biodiversity hotspot, harbouring a vast number of north-south oriented biodiversity corridor ecosystems. Kakku is located near several bird and wildlife sanctuaries. The nearest Inle Wetland Bird Sanctuary, for example, houses 345 bird species, 59 fish species, about thirty reptiles and amphibians and about 184 orchids. It is also suspected to be a nesting site for the endangered Sarus crane (Grus antigone). The Bodhi tree (ficus religiosa) is the most important plant species with religious value, as it is said that Buddha attained enlightenment under it. Its parts are used against about 50 ailments.

Custodians

The local Pa’oh people claim to own the Kakku pagoda complex. They have an appointed committee, the gawbaka, who have the responsibility and authority to manage the site. While the site has strong Buddhist significance, they express it also has spiritual and emotional meaning in the local animist religion, which sees the land as a domain of nats or spirits. The Pa’oh people migrated to the site around the 10th century A.D. They treated the site as a gathering point for annual celebrations and to express shared traditions, values and meanings.

The gawbaka was formed during the construction of the road to Kakku. It has 47 members appointed by former monk and political leader U Aung Kham Hti, based on religious qualifications. Decisions are made on consensus basis during the monthly meetings. Priority is placed mainly on the cultural and religious significance of the site for the Pa’oh people, who continue to use it as a site for worship, particularly during the Pa’oh holidays in March and November.

"While the gawbaka insists that Kakku is not a business and that it avoids tourism, the committee seems to have responded to development pressure… …The result has been a clearing of vegetation and accompanying wildlife, an increase in littering, and a rise in incidents involving tourists violating sacred rituals and rules."

- Liljeblad 2016.

Working together

The gawbaka works together with a range of governmental and non-governmental organizations, including the political party PNO, the Myanmar Government, foreign entities, private donors, worshippers and other visitors. Governmental organizations’ main concern is to improve the socio-economic conditions in Myanmar, and they promote rural development including the tourism industry. Indeed, the gawbaka acknowledges the benefits of such developments.

Conservation tools

To conserve the cultural heritage of Kakku, the gawbaka committee has increased security to monitor visitor behaviour. They also encourage monks to remind visitors of religious rules regarding worship. Tourists use site guides to educate them regarding the appropriate behaviour in the area. These efforts promote Pa’oh culture and spiritual practices, but are not particularly focused on nature conservation.

Results

The gawbaka feel that they so far have been able to preserve the sacred character of Kakku, particularly with respect to the behaviour of foreign tourists. They are, however, concerned about the management of Kakku in the face of efforts to promote greater tourism and socio-economic development, both of which will increase pressure on the environment and the pagodas at Kakku.

"Meetings with the gawbaka indicate some uncertainty regarding the origins of Kakku… …As a spiritual site, they note that within the Pa’oh culture the site itself has a significance outside Buddhism, with the land seen as a domain of nats, or spirits in Pa’oh animist beliefs" - Liljeblad 2016.

- Aung. Status of Biodiversity Conservation in Myanmar. Presentation for the CBD.

- Liljeblad, Jonathan. (2016) The Pa’oh’s Governance System and Kakku: Implications for Heritage Conservation from Burma/Myanmar, in Bas Verschuuren and Naoya Furuta (eds.), Asian Sacred Natural Sites: Philosophy and Practice in Protected Areas and Conservation. Routledge.

-

Contact:

Jonathan Liljeblad

Senior Lecturer, Law School

Swinburne University of Technology

H25 P.O. Box 218

Hawthorn, Victoria 3122 Australia